University of Michigan outdoes IBM with world's smallest 'computer'

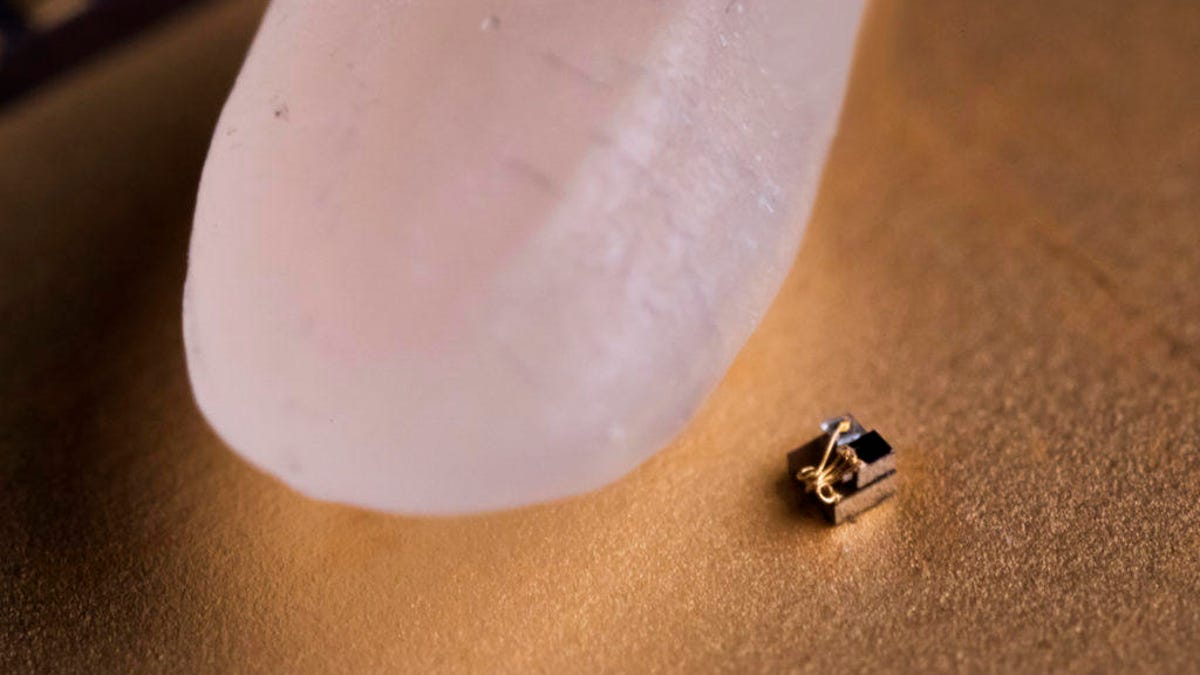

The computer, which can stand on the tip of a grain of rice, is one-tenth the size of IBM's version.

Engineers at University of Michigan have created a computer that could stand on the tip of a grain of rice.

In the world of tiny computing, the engineers at the University of Michigan just outdid IBM.

The university on Thursday said its engineers have produced a computer that's 0.3 mm x 0.3 mm -- it would be dwarfed by a grain of rice. While it drew comparisons to IBM's own 1mm x 1mm computer, Michigan's team said the creation is about more than just size.

"We are about 10x smaller so we can fit in smaller spaces," David Blaauw, a professor co-leading the project, said in an email statement. "Also, the IBM computer can't sense its environment -- it can send a code identifying itself but it does not sense its physical environment."

IBM didn't immediately respond to a request for comment.

U-M engineers held the record after creating the tiny Micro Mote in 2015. IBM, however, said in March that it had created the world's smallest computer, saying it was smaller than a grain of salt.

Going even smaller meant having to try new approaches.

"We basically had to invent new ways of approaching circuit design that would be equally low-power but could also tolerate light," said Blaauw.

The success of tiny computing opens doors for researches in other fields. You can use the little devices for pressure-sensing inside the eye, cancer studies, oil reservoir monitoring, biochemical process monitoring, tiny snail studies and more, according to University of Michigan.

"We're using the temperature sensor to investigate variations in temperature within a tumor versus normal tissue and if we can use changes in temperature to determine success or failure of therapy," said Gary Luker, a biomedical engineering professor collaborating with U-M's engineers, in the release.

However, the smaller-than-a-grain computer has limited features and its functionality would depend on what a specific study or activity needs, according to the university. In addition, it doesn't store data when it loses power, a trait it shared with the IBM computer.

"We are not sure if they should be called computers or not. It's more of a matter of opinion whether they have the minimum functionality required," Blaauw said.