That massive internet outage, explained

What even happened on Friday? Your favorite websites were down, and it was all because one company got attacked. Here's how it happened, and why it's likely to happen again.

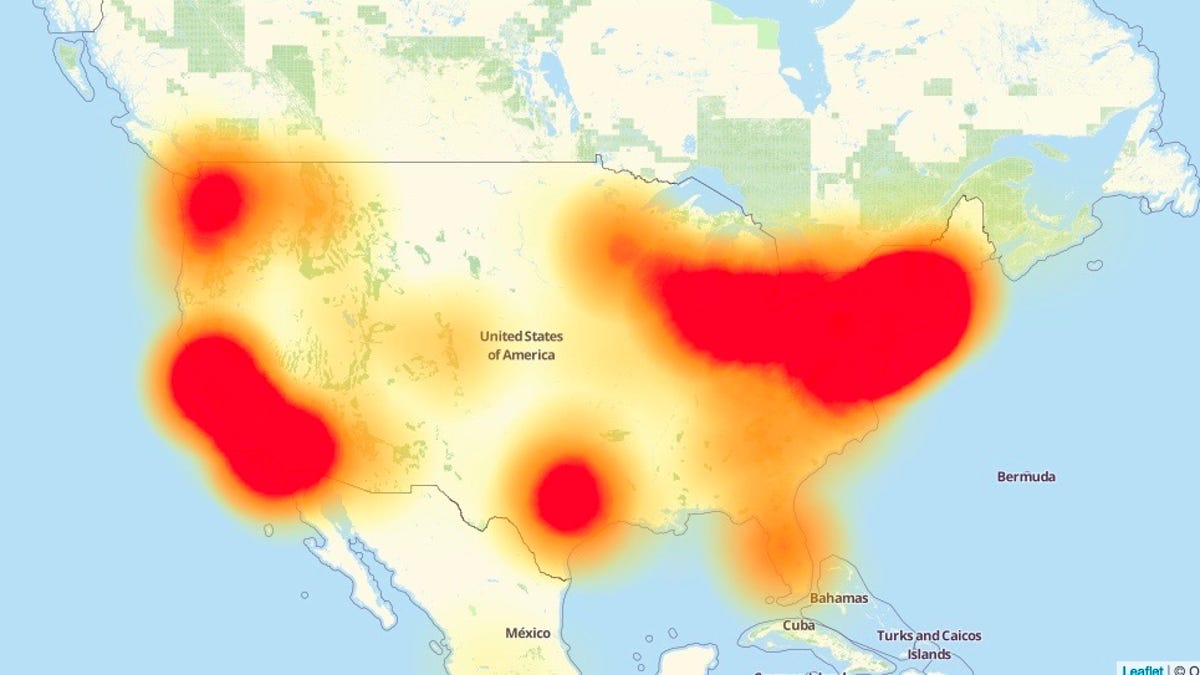

A map of the internet outage as it affected website access in the US at 11:30 a.m. Pacific Time on Friday.

If you've never heard of a DDoS attack before, you could be forgiven for wondering what the frak was going on Friday as half your favorite websites stopped working.

The acronym stands for "distributed denial of service attack," which is technical speak for a simple but increasingly powerful tool for knocking websites offline. Until recently, DDoS attacks were used to take down smaller targets and were often seen as the tools of activists and pranksters with a point to make.

But an attack that takes down multiple major websites for hours? That's no joke.

So what makes this kind of attack work, and how did it target all these sites at once? Here are the answers to your DDoS questions:

What is a DDoS attack?

A DDoS attack uses a variety of techniques to send countless junk requests to a website. This boosts traffic to the website so much that it gets overwhelmed, making it nearly impossible for anyone to load the page.

Websites have to filter out good traffic from bad, kind of like a dam that lets only so much water through. But if someone upstream can send an unexpected torrent down, the dam will overflow and maybe even crack, letting all the water through. That floods the area below -- and in our analogy, it drowns the website you're trying to reach. Now no one can go there.

Why are some sites (like Twitter and Spotify) affected, but not others?

Friday's attack targeted one company: Dyn Inc. That company manages web traffic for customers that include Twitter, Spotify, Netflix, Reddit, Etsy, Github and other favorites. Dyn is the dam for all these websites. So if a company uses Dyn to manage its web traffic, it could have been affected by the attack.

But if a company uses another service in addition to Dyn to manage its web traffic, it was likely spared the worst of outages.

Who is behind the DDoS attack?

We don't know who's responsible. The US Department of Homeland Security is investigating.

We do know that the attackers were using a hacked network of internet-connected devices to send all the requests. That network might have included devices like routers, security cameras or anything else the hackers found convenient to take over.

The hackers used malicious software called Mirai to infiltrate the devices, according to cybersecurity researchers at Flashpoint. That's the same software hackers used to create a massive botnet that sent the largest documented DDoS attacks ever and took down two different websites in September.

Is there any way to access sites under attack?

Yes. Here's a handy guide on how to reroute to the websites and dodge all this nonsense.

What have been the biggest DDoS attacks?

In September, attackers took down the website of cybersecurity writer Brian Krebs with the largest DDoS attack on record. The attack sent 620 gigabytes of data per second to his website. That was more than twice as big as the largest DDoS attack that occurred in the three months prior to the attack, according to a report from networking company Verisign.

But that incident was surpassed later in that same month by a DDoS attack on French web-hosting company OVH, which got slammed with multiple attacks at once, the largest of which sent 799 gigabytes of data per second to the site.

The hacker collective Anonymous is also known for using DDoS attacks against people and companies it deems worthy of scorn. That has ranged from Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump to banks in Greece.

Can companies adapt to protect themselves from future attacks like this?

Companies are already rethinking how to deal with DDoS attacks. Though tons of tools for dealing with DDoS attacks already exist, there have been signs all year that the strength of the attacks has been increasing.

The solution isn't obvious, because hackers will likely continue to build bigger and stronger botnets that can send more and more junk traffic. But now that it's gotten to a point where lots of sites can be taken down if they all use a service like Dyn, companies will have to rethink whether they should rely on just one major site management service. What's more, Google's Project Shield is specifically working to protect journalists like Krebs from DDoS attacks to prevent censorship.

"Companies should move immediately to get control of this situation," said Chris Sullivan, a researcher at cybersecurity firm Core Security. "In the wake of these new high-profile events, it's likely to be mandated by new law."

One other possible outcome of Friday's attacks could be that device manufacturers improve products that form the so-called internet of things. If the devices weren't so easy to hack, it's likely Friday's attack wouldn't have been so powerful.